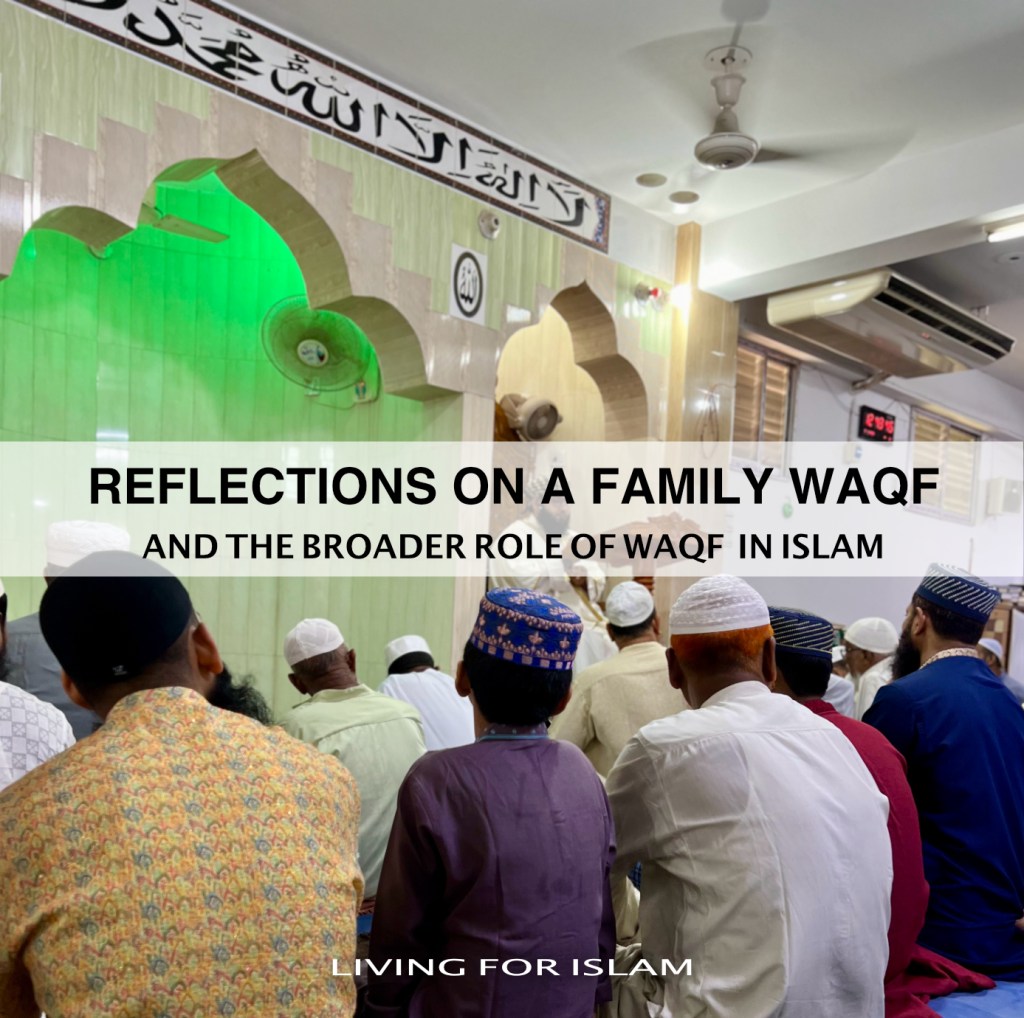

YESTERDAY, I ATTENDED Jumu‘ah at a masjid in Dhaka that holds deep personal significance for me. It was established by my parents in 2005 as a waqf—an Islamic endowment intended for perpetual public benefit. The last time I visited was in 2007, when the masjid was still a humble, tin-roofed, single-story structure in a developing neighbourhood.

Today, that same area has transformed into a thriving urban zone, and the masjid has grown alongside it. It now stands as a four-story permanent building that accommodates thousands of worshippers. It also includes facilities for women, a religious library, and a row of ground-floor shops whose rental income helps sustain the mosque’s operations. This income, along with community donations and my parents’ continued support, allows the masjid to run independently and effectively.

The fact that my parents chose to structure this institution as a waqf is significant and worth exploring in more detail.

What is Waqf?

In Islamic tradition, waqf (Arabic: وَقْف) refers to a permanent, irrevocable endowment of property or wealth for religious, educational, or charitable purposes. It is a deeply rooted institution in Islamic law and society, designed to ensure long-term benefit for the public while securing continuous spiritual reward for the donor.

Once something is designated as waqf—be it land, buildings, money, or other assets—it cannot be sold, inherited, or gifted again. Ownership belongs to Allah, and only the benefits of the asset may be used to serve a socially or religiously beneficial purpose.

Types of Waqf

1. Religious Waqf that supports masajid, madaris, and religious institutions.

2. Charitable Waqf (Waqf Khayri) to fund hospitals, schools, orphanages, and public infrastructure like wells.

3. Family Waqf (Waqf Ahli) in which the benefits go to the founder’s family, while the asset remains permanently dedicated.

Key Elements of Waqf

Waqif (Founder): The person donating the asset.

Mawquf (Asset): The item or property being endowed.

Mawquf ‘Alayh (Beneficiaries): The individuals or causes that benefit.

Purpose: Must be lawful (halal) and beneficial to society.

Permanence: Once declared, it cannot be revoked.

The Role of Waqf in Islamic Civilisation

Throughout Islamic history, waqf has played an important role in societal development. It served not only as a form of personal charity but also as a response to social needs.

Waqf has funded free hospitals, orphanages, housing, and food programs—offering a localised safety net.

Many of the Muslim world’s greatest institutions—like Al-Azhar in Cairo—were built and maintained through waqf. Libraries, student stipends, and teachers’ salaries were often paid through such endowments.

Hospitals funded by waqf provided services to the poor and travellers alike.

Waqf properties often generate income through rents or businesses. This economic activity supports jobs and reinvestment into the community.

Masajid, madaris, and religious scholars were often traditionally supported through waqf, preserving the religious fabric of society.

Islamic Foundations of Waqf

Although the Qur’an doesn’t mention waqf explicitly, its ethics are embedded in verses encouraging charity, generosity, and spending in the way of Allah:

لَن تَنَالُوا۟ ٱلْبِرَّ حَتَّىٰ تُنفِقُوا۟ مِمَّا تُحِبُّونَ

“You will never attain righteousness until you spend from that which you love…” (Ale-Imran 92)

مَّثَلُ ٱلَّذِينَ يُنفِقُونَ أَمْوَٰلَهُمْ فِى سَبِيلِ ٱللَّهِ كَمَثَلِ حَبَّةٍ أَنۢبَتَتْ سَبْعَ سَنَابِلَ فِى كُلِّ سُنۢبُلَةٍۢ مِّا۟ئَةُ حَبَّةٍۢ

The example of those who spend their wealth in the cause of Allah is that of a grain that sprouts into seven ears, each bearing one hundred grains. (al-Baqarah 261)

These verses highlight the principle of long-term, selfless giving—a core concept of waqf.

Furthermore, we find in the sunnah several narrations, most notably the incident involving Umar ibn al-Khattab (ra), who acquired land in Khaybar and consulted the Prophet ﷺ on what to do with it. The Prophet ﷺ advised him to endow it as waqf, stipulating that it not be sold, inherited, or gifted. The benefits were to serve the poor, travellers, and other public needs.

Many companions, such as Uthman ibn Affan (ra)—who purchased and endowed the famous well of Ruma, made similar endowments for the public good.

Legal Status in Islamic Jurisprudence

All four major Sunni madhhabs (Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi‘i, Hanbali) recognise waqf as a binding and virtuous act. It is seen as a form of sadaqah jāriyah, an ongoing charity whose benefits continue even after the donor’s death.

The Messenger ﷺ said, “When a person dies, their deeds come to an end except for three: ongoing charity, beneficial knowledge, or a righteous child who prays for them. (Muslim)

Waqf offers a structured, enduring way to fulfil this prophetic teaching.

Colonial and Modern Disruptions

It is interesting to note that during British colonial rule in India, waqf institutions were undermined through legal reforms that imposed Western property laws. This disrupted traditional Islamic infrastructure, weakening the economic and social base of Muslim communities and making us more reliant on Western institutions whilst enriching the colonists.

In more recent times, the Indian government’s reforms under the Modi administration have raised new concerns. While aiming to increase transparency, these laws also interfere with the autonomy of Muslim religious institutions and endanger the integrity of waqf assets.

Reviving Waqf in the Modern World

Today, many Muslim-majority countries are attempting to revive the waqf system as a means of addressing modern challenges such as reducing poverty, supporting education and healthcare and promoting sustainable charitable giving over one-time donations

The waqf system, if managed ethically and transparently, has immense potential to meet local needs—especially in underserved areas.

The Limits of Waqf – And the Need for Islamic Governance

Despite its strengths, waqf is not a substitute for state responsibility. Eradicating poverty, providing universal healthcare, ensuring access to education, and safeguarding housing and food security are duties that fall squarely on the shoulders of the state.

In many cases, modern Muslim states—secularised and detached from Islamic values—have failed to fulfil these obligations. As a result, the burden has shifted unfairly onto individuals and charitable institutions like the waqf. While waqf fills important gaps, it cannot create the justice, scale, or coordination that only a rightly guided Islamic government can provide.

Conclusion

My parents’ initiative in founding a waqf-based masjid is a beautiful example of how personal charity can ripple into lasting community benefit. It is also a reminder of Islam’s deeply rooted traditions of structured, sustainable giving.

But as we reflect on these legacies, we must also confront the reality: charity alone is not enough. The full realisation of Islamic social justice requires not only individual virtue but also institutional reform and the revival of an Islamic political framework at the heart of governance.